The first studies and the observations of patterns in the ratio of the products and reactants were made in 1864 by Norwegian mathematician Cato Guldberg and a chemist Peter Waage when working on reactions of gases.

They noticed that in a reaction between gas molecules, the ratio of the partial pressures of the products over the product of the partial pressures of reactants raised to the power of their coefficients stays constant no matter what the initial amounts of were. This was how the expression for the equilibrium constant was derived.

For example, when sulfur dioxide was mixed with oxygen, it was found the following ratio of the partial pressures is always the same number:

2SO2(g) + O2(g) ⇆ 2SO3(g)

\[{K_p} = \frac{{{P^2}_{{\rm{S}}{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{3}}}}}}{{{P^{\rm{2}}}{{_{{\rm{SO}}}}_{_2}}{P_{{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{2}}}}}}}\]

Where PSO3, PSO2, and PO2 are the partial pressure of the reaction components.

The subscript p on K is used to point out that the equilibrium constant Kp is defined using partial pressures.

The equilibrium constant can also be expressed in terms of the molar concentrations:

\[{K_c} = \frac{{{{\left[ {{\rm{S}}{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{3}}}} \right]}^2}}}{{{{\left[ {{\rm{S}}{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{2}}}} \right]}^2}\left[ {{{\rm{O}}_{\rm{2}}}} \right]}}\]

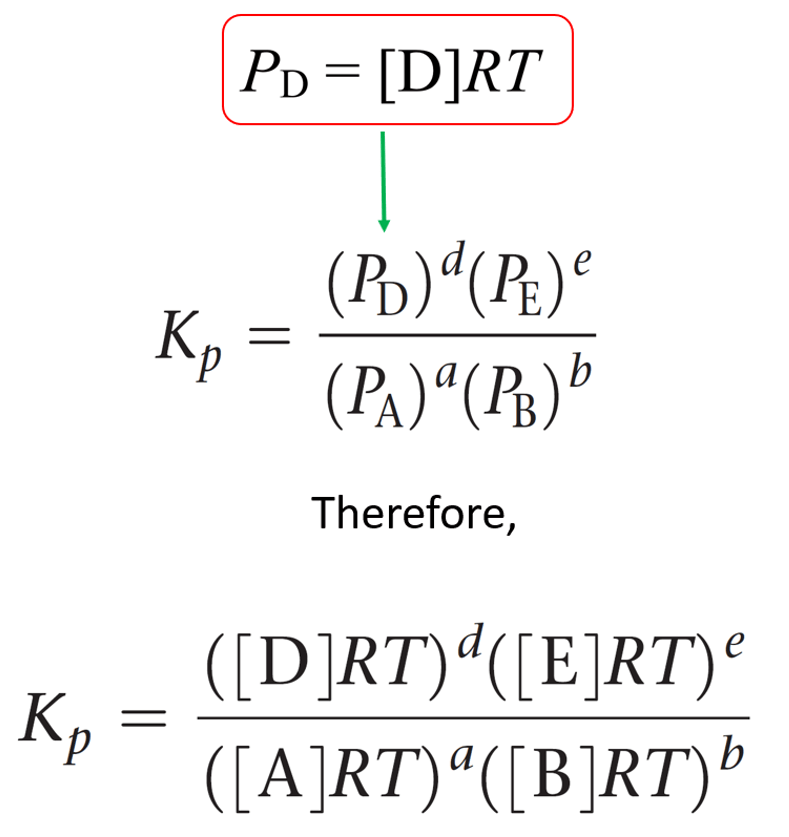

The values of Kp and Kc are often different, however, we can calculate one from the other based on the coefficients of the balanced chemical equation. We will cover this in the next article.

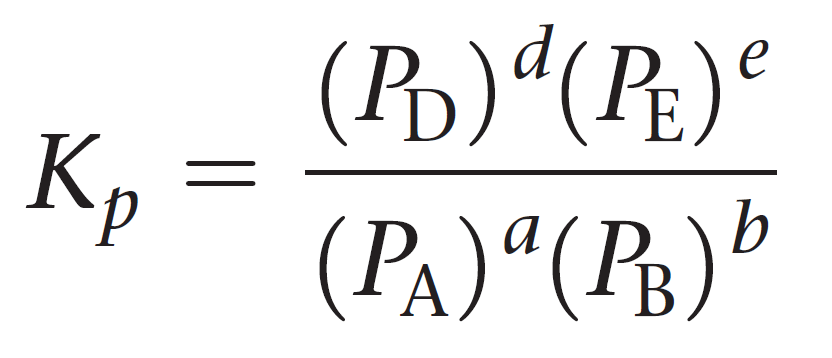

For a general reaction of gases, the equilibrium constant Kp can be represented as:

aA + bB ⇆ cC + dD

Let’s see an example of calculating Kp.

Example:

The following equilibrium pressures were observed at a certain temperature for the Haber process:

3H2(g) + N2(g) ⇆ 2NH3(g)

P(NH3) = 5.2 x 109 atm

P(N2) = 6.1 x 102 atm

P(H2) = 4.7 x 103 atm

Calculate the value for the equilibrium constant Kp at this temperature.

Solution:

\[{K_p} = \frac{{{P^2}_{{\rm{N}}{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{3}}}}}}{{{P^3}_{{{\rm{H}}_{\rm{2}}}}{P_{{{\rm{N}}_{\rm{2}}}}}}}\]

\[{K_p} = \frac{{{{(5.2 \times {{10}^9})}^2}}}{{{{(4.7 \times {{10}^3})}^3}(6.1 \times {{10}^2})}} = 4.3 \times {10^5}\]

As for the Kc, the expression and value of Kp depend on the chemical equation, mainly the coefficients and the direction of the reaction.

Let’s see how these are related.

Kp for the reverse reaction

The following reaction has an equilibrium constant of Kp = 4.42 x 10-5 at 298 K:

CH3OH(g) ⇆ CO(g) + 2H2(g)

Calculate the equilibrium constant for this process if the reaction is represented as follows:

CO(g) + 2H2(g) ⇆ CH3OH(g)

Remember, when a reaction is reversed, then Knew = 1/Koriginal.

Therefore,

Knew = 1/Koriginal= 1/4.42 x 10-5= 22,624.43 = 2.26 x 104

Kp When the Coefficients are Changed

Based on the Kp value given above, what is the Kp for the following reaction?

2CH3OH(g) ⇆ 2CO(g) + 4H2(g)

Comparing this equation to the original, we see that it is multiplied by 2. Remember when the coefficients in the equation are multiplied by any factor, we raise the equilibrium constant to the same factor. Therefore,

Knew = (Koriginal)n = (4.42 x 10-5)2= 1.96 x 10-9

Practice

Consider the following reaction at 298 K:

2NO(g) + Cl2(g) ⇆ 2NOCl(g) Kp = 31.6

In a reaction mixture at equilibrium, the partial pressure of NO is 128 torr and that of Cl2 is 176 torr. Calculate the partial pressure of NOCl at equilibrium.

Check Also

- Chemical Equilibrium

- Equilibrium Constant

- Kpand Partial Pressure

- Kp and KcRelationship

- K Changes with Chemical Equation

- Equilibrium Constant K from Two Reactions

- Reaction Quotient – Q

- ICE Table – Calculating Equilibrium Concentrations

- ICE Table Practice Problems

- Le Châtelier’s principle

- Le Châtelier’s principle Practice Problems

- Chemical Equilibrium Practice Problems