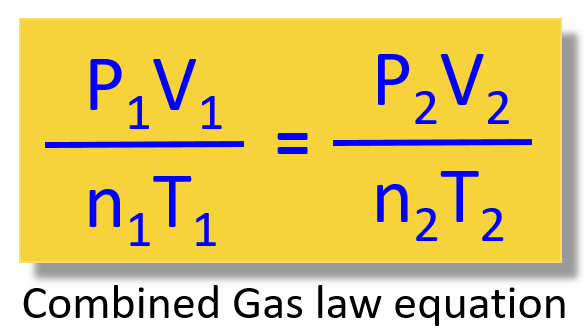

“Do we have to convert the Celsius to Kelvin?” is the question that I probably heard the most common when solving practice problems on gas laws in class.

And the short answer is yes, it is almost always necessary to convert the units of temperature to Kelvin. The reason for this is the units of the gas constant R. Although it may have different units depending on the units of the pressure and volume, in chemistry, it is most often going to be

\[R\;{\rm{ = }}\;{\rm{0}}{\rm{.08206}}\;\frac{{{\rm{L}} \cdot {\rm{atm}}}}{{{\rm{mol}} \cdot {\rm{K}}}}\]

For example, a sample of hydrogen gas is added in a 5.80 L container at 56.0 °C. How many moles of the gas are present in the container if the pressure is 6.70 atm?

Let’s first write down what we are given:

V = 5.80 L

T = 56.0 oC

P = 6.70 atm

n(H2) = ?

T = 273 + 56.0 = 329 K

To find the moles of hydrogen, we need the ideal gas law equation:

PV = nRT

\[{\rm{n}}\;{\rm{ = }}\;\frac{{{\rm{PV}}}}{{{\rm{RT}}}}\]

\[{\rm{n}}\;{\rm{ = }}\;\frac{{{\rm{6}}{\rm{.70}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{atm}}}}\; \times \;{\rm{5}}{\rm{.80}}\;\cancel{{\rm{L}}}}}{{{\rm{0}}{\rm{.08206}}\;\cancel{{\rm{L}}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{atm}}}}\;\cancel{{{{\rm{K}}^{{\rm{ – 1}}}}}}\;{\rm{mo}}{{\rm{l}}^{{\rm{ – 1}}}}{\rm{ }} \times \;{\rm{329}}\;\cancel{{\rm{K}}}}}\; = \;1.44\;{\rm{mol}}\]

Notice how having the units in K allowed us to cancel them out.

The take-home message is whenever you are using a formula with R = 0.08206 L · atm / K · mol, change the units of temperature to Kelvin.

What Happens if I don’t Convert to Kelvin?

Let’s say you are working on a problem that does not use the ideal gas law equation.

For example, a gas sample is stored in a 429 mL container at 9.50°C and 2.20 atm. Calculate the pressure of the gas if the volume changes to 134 mL and the container is heated to 134.5 °C? Assume a constant amount of gas.

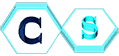

First, remember what we discuss about choosing the correct gas law. Instead of trying to remember which one to use, go with the combined gas law equation.

Write it down and remove the quantities that are not mentioned in the problem.

In this case, we have:

V1 = 429 mL

V2 = 134 mL

P1 = 2.20 atm

T1 = 9.50 oC

T2 = 134.5 oC

P2 = ?

Remember, the temperature must always be converted to K in gas problems, and we will see why in a second.

T1 = 9.50 + 273 = 282.5 K

T2 = 134.5 +273 = 407.5 K

Next, write the combined gas law equating and get rid of the constants. In this case, only the moles of the gas are constant:

\[\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{1}}}}}{{{{\rm{n}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{1}}}}}\; = \;\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{2}}}}}{{{{\rm{n}}_{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{2}}}}}\]

\[\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{1}}}}}{{{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{1}}}}}\; = \;\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{2}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{2}}}}}{{{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{2}}}}}\]

\[{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{2}}}\; = \;\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{2}}}}}{{{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{2}}}}}\]

\[{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{2}}}\; = \;\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{2}}}}}{{{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{2}}}}}\; = \;\frac{{{\rm{2}}{\rm{.20}}\;{\rm{atm}}\;{\rm{ \times }}\;{\rm{429}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{mL}}}}\;{\rm{ \times }}\;{\rm{407}}{\rm{.5}}\;\cancel{{\rm{K}}}}}{{{\rm{282}}{\rm{.5}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{K}}\;}}\;{\rm{134}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{mL}}}}}}\;{\rm{ = }}\;{\rm{10}}{\rm{.2}}\;{\rm{atm}}\]

Notice that we did not need to convert the ml to L because they cancel out in the equation. The volume must be in L though when the R, expressed using L, is part of the calculation.

So, let’s say we did not convert the units of T to Kelvin. The answer would have been:

\[{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{2}}}\; = \;\frac{{{{\rm{P}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{2}}}}}{{{{\rm{T}}_{\rm{1}}}{{\rm{V}}_{\rm{2}}}}}\; = \;\frac{{{\rm{2}}.{\rm{20}}\;{\rm{atm}}\; \times \;{\rm{429}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{mL}}}}\; \times \;{\rm{134}}.{\rm{5}}\;\cancel{{\rm{K}}}}}{{{\rm{9}}.{\rm{5}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{K}}\;}}\;{\rm{134}}\;\cancel{{{\rm{mL}}}}}}\;{\rm{ = }}\;99.7\;{\rm{atm}}\]

We are getting a wrong answer when the units of temperature are not in Kelvin.

The difference between volume and temperature is that for the volume, we multiply or divide by 1000 when converting between ml and L, while for temperature, we add 273 which does not change both numbers with an equal magnitude.

To illustrate this, consider a simple example. Six divided by 2 is 3, and if we multiply both parts of the fraction by 20, we are going to get the same answer. However, if we add 20 to each part of the fraction, like we do for temperature, the answer is going to be different.

To summarize, always convert the temperature to Kelvin when using a gas law problem. The exceptions would be when R is different than 0.08206 L · atm / K · mol.

How are the Units and Value of R Obtained?

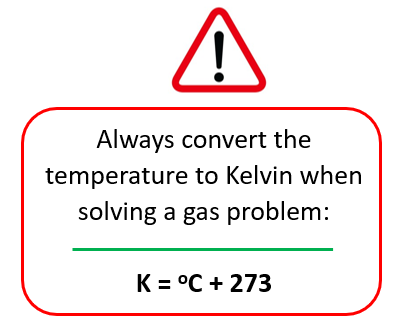

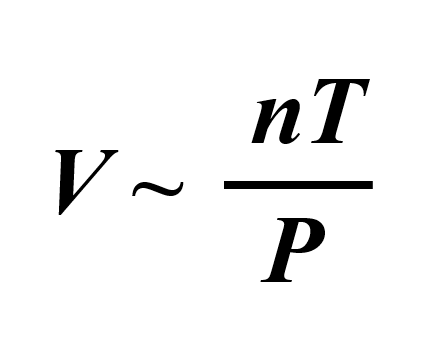

Let’s for a moment go back to how we derive the ideal gas law equation to see where the units of R are coming from. The ideal gas law is derived from the individual gas laws such as the Boyle’s law, Charles’ law, etc. Remember, when discussing those, we used a pump with a freely moving plunger and by changing the parameters one by one, we were able to get the following correlations:

We can combine all of these to get an expression showing how, for example, the volume of an ideal gas is correlated to the temperature, pressure, and the moles of the gas:

To bring in the equal sign, we then introduce a constant:

This can be explained using the example of a car dealership income. The income depends on the number of sales which we can represent as:

income ~ number of cars sold

However, we cannot say income = number of cars sold, so to switch an equal sign, we need to introduce a constant. This can be the price of the car transforming the equation to:

Income = price x number of cars

Now, for the parameters of ideal gases, the constant is the R, which is the ideal gas constant that has the same value for all gases because it is independent of the identity of the gas:

\[V\;{\rm{ = }}\,R\, \times \,\frac{{nT}}{P}\]

And finally, by rearranging it, we obtain the ideal gas law equation:

Now, we can also rearrange the ideal gas law equation to get an expression for the R:

\[R\;{\rm{ = }}\,\frac{{PV}}{{nT}}\]

Conventionally, the units for pressure are atm, volume is given in liters, the SI unit of temperature is Kelvin, and for the amount of chemicals is moles. Therefore, the units of R would be:

\[R\;{\rm{ = }}\,\frac{{PV}}{{nT}}\; = \,\frac{{{\rm{atm}}\, \cdot \,{\rm{L}}}}{{{\rm{mol}}\, \cdot \,{\rm{K}}}}\]

How do we obtain the numeric value of R?

Theoretically, we could use any quantity of any ideal gas, measure its volume and pressure, and plug in these numbers to obtain the value of R. However, to keep a standard and consistency, this is done for a gas at standard temperature and pressure, often abbreviated STP. This is when we have one mole of an ideal gas at 0 oC (273.15 K) and 1 atm pressure. It is shown experimentally that under these conditions, 1 mole of an ideal gas occupies 22.414 L, which is called the molar volume of the gas.

Using these numbers, a numeric value and units of R can be obtained:

\[R\;{\rm{ = }}\,\frac{{PV}}{{nT}}\; = \,\frac{{{\rm{(1}}\,{\rm{atm)}}\,{\rm{(22}}{\rm{.414 L)}}}}{{{\rm{(1}}\,{\rm{mol)}}\,{\rm{(273}}{\rm{.15}}\,{\rm{K)}}}}\]

\[R\;{\rm{ = }}\,{\rm{0}}{\rm{.08206}}\frac{{{\rm{atm}}\, \cdot \,{\rm{L}}}}{{{\rm{mol}}\, \cdot \,{\rm{K}}}}\]

As you may wonder, this is not the only value of R because we can change for example the units of pressure. For example, when we use the SI units for pressure and volume as well (pascals and meters cubed respectively), R is obtained in joules per kelvin per mole: R = 8.314 J · K-1 · mol-1.

For most general chemistry classes, you are going to use the R = 0.08206 L · atm / K · mol.

And here are some summary gas law problems and if you are not sure how to start, make sure to check the articles on the gas law chapter.

Check Also

- Boyle’s Law

- Charle’s Law

- Gay-Lussac’s Law

- Avogadro’s Law

- The Ideal Gas Law

- Ideal-Gas Laws

- Combined Gas Law Equation

- How to Know Which Gas Law Equation to Use

- Molar Mass and Density of Gases

- Graham’s Law of Effusion and Diffusion

- Graham’s Law of Effusion Practice Problems

- Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures

- Mole Fraction and Partial Pressure of the Gas

- Gases in Chemical Reactions

- Gases-Practice Problems

Practice

The pressure of a gas is 2.30 atm in a 1.80 L container. Calculate the final pressure of the gas if the volume is decreased to 1.20 liters.

After changing the pressure of a gas sample from 760.0 torr to 0.800 atm, it occupies 4.30 L volume. What was the initial volume of the gas?

What will be the final volume of a 3.50 L sample of nitrogen at 20.0 °C if it is heated to 200. °C?

The volume of a gas decreased from 2.40 L to 830. mL and the final temperature is set at 40.0 °C. Assuming a constant pressure, calculate the initial temperature of the gas in kelvins.

A sample of helium gas at 1.40 atm is heated from 23.0 °C to 400.0 K. How many atmospheres is the final pressure of the helium gas?

A sample of hydrogen gas is added in a 5.80 L container at 56.0 °C. How many moles of the gas are present in the container if the pressure is 6.70 atm?

What is the pressure in a 26.0 L container with 5.40 moles of nitrogen dioxide if the temperature is 64.0°C?

A 3.7 L gas sample, initially at STP, is heated to 280. °C at constant volume. Calculate the final pressure of the gas in atm.

A 2.65 g sample of dry ice (solid carbon dioxide) is placed in a 2.90-L vessel and converted into CO2 gas. Calculate the pressure inside the vessel if the temperature is at 35.0 oC.

A gas sample is stored in a 429 mL container at 9.50°C and 2.20 atm. Calculate the pressure of the gas if the volume changes to 134 mL and the container is heated to 134.5°C? Assume a constant amount of gas.

A gas sample occupies 22.0 L at 171°C and 1.43 atm. Calculate the volume of the gas if its temperature and pressure are increased to 197 °C and 1.80 atm respectively.

A sample of ethylene gas (C2H6) collected in a 36.4 mL vessel with a freely moving piston, at 31.0 °C exerts 745 mmHg pressure. What is the volume of this gas at STP?

A gas-filled balloon having a volume of 3.50 L at 1.30 atm and 25.0 °C is allowed to rise 5 km above the surface of Earth, where the temperature and pressure are 12.0 °C and 1.10 atm, respectively. What would the volume of the balloon be in these conditions?

What is the density of CO2 gas at 386 K and 17.0 atm.

Determine the density of ammonia gas, NH3, at 36.0 oC and 695 mmHg. Report the density in grams per liter.

A scientist carries out an experiment to determine the molar mass of a 2.84-g sample of a colorless liquid which exerts 756 mmHg pressure when vaporized in a 260-mL flask at 142 oC. What is the molecular mass of this compound?

Identify the unknown gas that weighs 17.75 grams in a 17.0 L cylinder held at 0.700 atm pressure and 250°C.

a) NO2 b) CO2 c) H2 d) SO2 e) He

What is the ratio of the effusion rates of hydrogen gas (H2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) at the same pressure and temperature?

The rate of effusion of an unknown gas is 9.20 mL/min. Under identical conditions, the rate of effusion of pure nitrogen (N2) gas is 14.65 mL/min. Identify the unknown gas using the Graham’s law.

a) O2 b) C3H8 c) C4H10 d) NO2 e) Cl2

A sample of krypton effuses from a container in 95 seconds. The same amount of an unknown gas requires 55 seconds. Identify the unknown gas.

If a sample of Br2 vapor can effuse from an opening in a heated vessel in 46 s, how long will it take the same amount of He to effuse under identical conditions?

It has been demonstrated that 3.56 mL of an unknown gas effuses through a hole in the same time that 8.64 mL of argon does under the same conditions. Determine the molecular mass of the unknown gas.

What is the partial pressure of nitrogen in a mixture of N2, SO2 and CO2 that has a total pressure of 6.84 atm. The partial pressure of SO2 is 2.10 atm, and the partial pressure of CO2 is 1.74 atm.

13.2 grams of CO2 and 6.00 grams of He are mixed in a 4.00 L container at 300. K. Calculate the partial pressure of both gases and the total pressure of the mixture.

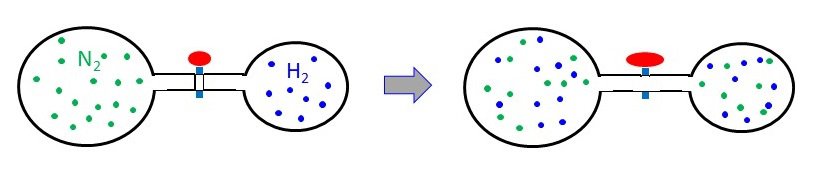

A 3.00-L bulb containing N2 at 1.80 atm pressure is connected to a 2.00-L bulb filled with H2 at 3.50 atm pressure. What is the final pressure of the system when the valve is opened?

Assuming ideal gas behavior, calculate the total pressure (in atm) of a mixture of 0.0260 mol of nitrogen, N2, and 0.0170 mol of argon, Ar, in a 3.50-L flask at 20 oC.

A mixture of gases contains CH4, N2, and H2 and exerts a total pressure of 2.65 atm. The mixture contains 0.456 mol of CH4, 0.540 mol of N2 and 0.730 mol of H2. What is the partial pressure of hydrogen in atmospheres?

The partial pressures of CH4, C3H8, and C4H10 in a gas mixture are 270 torr, 1016 torr, and 1142 torr, respectively. What is the mole fraction of butane (C4H10)?

In a mixture of two gases, the partial pressure of CO2(g) is 0.145 atm and that of O2(g) is 0.370 atm.

a) What is the mole fraction of each gas in the mixture?

b) Calculate the total number of moles of gas in the mixture if the mixture occupies a volume of 12.5 L at 45.0 °C.

c) Calculate the number of grams of each gas in the mixture.

Oxygen can be prepared in the laboratory by decomposing potassium chlorate, KClO3 according to the following reaction:

2KClO3(s) → 2KCl(s) + 3O2(g).

How many liters of oxygen can be produced from 4.80 g KClO3, if the reaction is carried out at standard conditions?

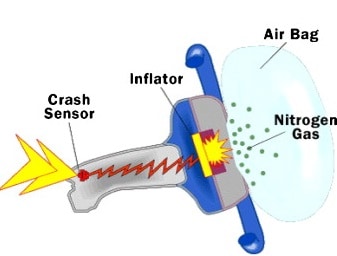

Sodium azide is used in automobile airbags as a source of nitrogen gas to rapidly inflate the bags upon a hit. If the volume of the airbag is 7.95 L, what mass of NaN3 is required to produce enough nitrogen to fill it at 23.0 °C and 1.20 atm?

2NaN3(s) → 2Na(s) + 3N2(g)

Calcium hydride (CaH2) can be used as a drying agent and a source of Hydrogen, because of its high reactivity with water.

CaH2(s) + 2 H2O(l) → Ca(OH)2(aq) + 2H2(g)

How many grams of CaH2 are needed to produce 76.8 L of H2 gas at a pressure of 0.750 atm and a temperature of 25 °C?

Propane (C3H8) is used as a fuel in gas barbecue grills. How many liters of oxygen, taken at STP, are needed for the full combusting of 26.4 g of propane?

C3H8(g) + 5O2(g) → 3CO2(g) + 4H2O(l)

Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is used in space shuttles to absorb the carbon dioxide exhaled by astronauts according to the following equation:

2LiOH(s) + CO2(g) → Li2CO3(s) + H2O(l)

How many liters of carbon dioxide gas at 23.0 oC and 732 mmHg could be absorbed by 284 g of lithium hydroxide?

In a particular reaction, at 25 °C, 16.4 L of carbon monoxide at a 950.0 torr is mixed with 11.2 g of iron (III) oxide, and 5.68 g iron is obtained. What is the percent yield of the reaction?

Fe2O3 + 3CO(g) → 2Fe + 3CO2(g)